Jordan Peterson’s Manifesto: Shallow Gobbledygook, but Still Horrifying

Jordan Peterson may be the most innovative and prominent conservative thinker of our time. I have already talked about how this is more so a sad reflection of the dearth of modern conservative thought than a compliment towards his introspective abilities, but he’s still an important person to grasp in order to understand modern conservatism.

Recently, he took it upon himself to post two videos reading out his Vision for Conservatives: a Conservative Manifesto. I personally find it a bit hard to watch. He has an odd tendency to shout and take a very aggressive and haughty posture while speaking. His language is needlessly flowery, and often times he’ll undermine his own point by prioritizing sounding fancy over being compelling. For example, when trying to sell us on marriage, he calls it “a difficult, challenging, mature enterprise.” This is what I want out of my career in business management development, not my love life.

The first part of this Manifesto is fairly unoffensive. I could point out Peterson’s persistent failure to understand or even conceptualize his opponents, his habit of talking authoritatively on topics he clearly knows nothing about, or that one time he had to stare at the middle distance for a few seconds before waffling about not wanting to call himself a prophet, and how that undermines his very first point, which is about humility. I could make a long-winded critique of his blind trust in “free-market” capitalism and how it tends to undermine many of his other values. Or, I could talk about his preference for “spontaneous responses,” which I assume refers to live debate, and how this ignores the demagoguery and misleading rhetoric that has been a problem as old as ancient Athens, and one which the right is often criticized for weaponizing.

What (right wing pundit) Ben Shapiro does is effectively the debate equivalent of an average quality sprinter exclusively challenging children to races where he gets extra time and then going “look, I won most of these matches; I must be the greatest player of all time!” — Sarah Z

Overall, I find the first part of Peterson’s manifesto an agreeable explanation of conservative values. The second part is where it gets interesting. He starts off with a complete bombshell on “material privation and the unequal distribution of both resources and rewards.” Right off the bat, he makes a mystical argument about nature.

The equally brute fact of disproportionate gain and loss is neither attributable in the most fundamental sense to the inadequacies of individual aim or the insufficiency of communal institution. It is, instead, something deeply and mysteriously built into the structure of natural reality itself, both natural and social. — Jordan Peterson

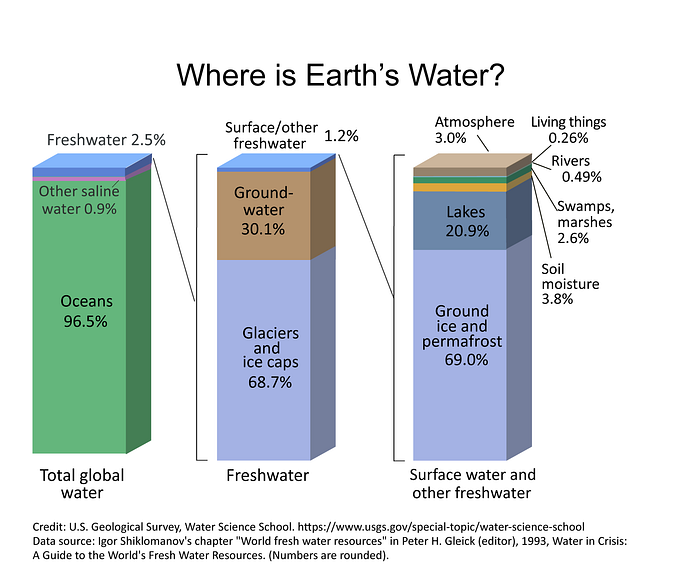

For Jordan Peterson, our modern struggle with economic inequality is not a result of systems designed by humans, but a fact of life woven into the very fabric of the universe. “A small number of stars have most of the mass… a small number of rivers carry most of the world’s water… a small number of cities have the majority of people… a small number of earthquakes destroy the most buildings… a small number of classical composers wrote all of the music of the common classical repertoire… a small fraction of scientists publish the majority of scientific papers, a small number of scientific papers accrue the majority of citations… a small number of authors dominate the bestseller charts… a small number of people in every enterprise undertake the vast bulk of the valuable work.”

The claim that inequality of production is fundamental to the nature of the universe is a spectacular claim that needs much better evidence to be taken seriously. Instead, we should look specifically into claims about human inequality and think critically about where it may come from. For example, publications and citations in scientific journals are not the objective measures of productivity they appear to be. Profit-driven journals often require researchers pay thousands of dollars to be published, while “citation cartels” create a tight in-group of researchers who juke their own stats by citing each other or even themselves constantly.

Focusing on publications in the first place ignores non-research sources of productivity and value like mentorship, scientific communication, advocacy, and research infrastructures. Then, there’s the well-known Matthew effect of accumulated advantage, which basically describes how the “rich get richer” because initial advantages lead to a snowball of more success. This was originally used to describe famous researchers who receive credit for big ideas even when lesser-known researchers published findings on them first. Kids who are labeled “special needs” in school may experience a decline in IQ scores: an accumulated disadvantage that ruins their chance of entering academia in the first place. This is all to say that even in a relatively objective and meritocratic domain like science, it’s possible that the distribution of rewards has more to do with social structures than innate differences in the ability of human beings.

In his own clumsy and uninformed way, I think Peterson is trying to describe the presence of power laws like the so called “Pareto Principle,” which asserts that in some situations 20% of the cause produces 80% of the results. For example, 80% of sales may come from 20% of customers, or 20% of the errors in a piece of software may lead to 80% of crashes. The Pareto Principle seems to be a general piece of wisdom in the business community that I haven’t really been able to find rigorous evidence for. Universal “organizing principles” for complex networks are very controversial in general.

Granting that there’s some truth to Peterson’s non-mystical claim that “every known productive and creative endeavor produces an inequality,” we have to question where these inequalities come from, and whether fundamentally changing them might be for the better. Radio stations blasting Despacito 24/7 all over the planet for months may have been the “natural” outcome of our profit-driven global market economy, but it didn’t reflect the quality of what was ultimately a mediocre song, nor did I enjoy living in that world. As a musician myself I prefer that the market be spread out between a diverse array of talented musicians rather than dominated by a few well-connected individuals.

Returning to the Matthew Effect, it’s a massive leap to conclude that because we can statistically tie a few people to the most sales or citations or whatever, a tiny group of people are responsible for most of the value. For example, Shakespeare is often credited with having invented up to 1,700 words. Since Shakespeare lived during a period where the English language was changing incredibly quickly and there were very few written sources, it’s more likely that the vast majority of these words were being spoken by the general population before he happened to write them down in a work that survived to the present day. This is to say, that sometimes only the most famous mouthpieces get credit for using innovations developed by collaborations between the great mass of people.

Jordan Peterson is a big proponent of hierarchies based on what he believes to be the innate characteristics of people, like ranking and sorting people by their IQ scores. This is to say, he believes people who score higher on IQ tests are inherently more productive humans who naturally receive more benefits for their outstanding contributions to society. In contrast, “the relationship between poverty and intelligence is self-evident,” and some people are basically too stupid to meaningfully contribute to a modern complex society.

To counteract what he considers a tragic and inevitable fact of life, he encourages the talented few to be both productive and generous. He argues that service to the “poor, downtrodden, marginalized, and infirm” is “the most valid and reliable source of the meaning that most truly sustains us all, protecting us from despair.” This is to say, that our society should produce noble people of extraordinary power who use the rewards of their genius to prevent people with limited ability to contribute from becoming completely destitute. In other words, Bill Gates.

Especially within Peterson’s meaning-driven philosophy, I find this to be worse than a mere inequality of rewards. Not only are people dependent on the benevolence of the powerful to meet their basic needs, they now function primarily as a source of meaning for those few powerful people, with no way to achieve a valid and reliable meaning of their own. Peterson is advocating not only for an inequality of rewards and recognition but of meaning itself.

If David Graeber’s Bullshit Jobs has any merit, some of you may already have a visceral experience of this inequality of meaning. Peterson’s meteoric rise is arguably a result of it. He proposes some solutions to the average person’s crisis of meaning: marriage, family, friends, a job. Ultimately, however, he has always made it clear that power and the truly great sources of meaning are reserved for the talented upper class.

Whoever wants to be first must be slave of all. For even the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many. — Mark 10:44–45

Traditionally, the primary political project of the left has been to empower the underclass. The Marxist motto “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs” sounds similar to what Peterson advocates for, and in some ways it is, especially when considered in light of its Christian roots (the early Christians held all of their possessions in common). What his system lacks, however, is a willingness to distribute actual power to those down the chain, to hand over the means of producing meaning to those lower down on the pecking order. This is a fundamental if not the fundamental difference between the right and the left.

For example, before being purged by Stalin, scientists in the Soviet Union built a curriculum for children who were both blind and deaf, intended to foster independence, self-sufficiency, and adaptation to their unique condition. During the “Zagorsk experiment”, four deaf-blind foster children of Zagorsky boarding school enrolled at the Moscow State University and graduated with the MS Psychology degree using special learning techniques developed by Sokolyansky and Meshcheryakov. Unsurprisingly, deaf-blind superstar Helen Keller was an avid socialist. In contrast, founding father of AT&T and inventor of the telephone Alexander Graham Bell lobbied for isolating and segregating deaf people to prevent them from being successful, finding love, and passing down their supposedly inferior genetics to the next generation.

I won’t say that Peterson advocates for eugenics, but I think he provides a clear path to that line of thinking, which explains why he had a friendly discussion with white supremacist and eugenicist Stefan Molyneux about IQ and genetics.

He presents us with the following conundrum: The best predictors of success are intelligence and conscientiousness. IQ science has found that there are “profound and virtually irremediable differences” in cognitive performance that are both biological and heritable. This means that there is a natural and unfixable difference between the performance of different individuals and even races in our society. People with an IQ under 83 cannot be trained to perform basic productive tasks (the Bell Curve, which Peterson cites, places the average IQ of black people at around 85 or lower). So, we have the “terrifying” prospect that about 10% of our society has no prospect of gainful employment.

Jordan Peterson doesn’t provide us with a solution to this problem, merely poses the question and says “no one knows” what to do about it. We can’t “shovel money down the hierarchy” because these people are basically too stupid to manage money. He claims it’s fundamentally impossible to train the bottom 10% of humanity to function in a cognitively complex society. So, the only options he really leaves us with are to leave a class of miserable people incapable of living meaningful lives begging and dependent on the noble ruling class, or eliminate these people from the gene pool.

I have already implied that IQ in fact is not as fixed as Peterson claims, and the idea that IQ serves as a fatalistic predictor of one’s station in life is demonstrably false. Peterson ultimately advocates for prejudice using bunk science. Even if it were true, our obligation as a society would be to empower the bottom 10% and invest our resources to give them independence and a reliable source of purpose, not to encourage power being concentrated with the fortunate few at the top.

My mom has crippling Multiple Sclerosis that makes it impossible for her to do most physical tasks. Yet, with the support of her community and the government, she has managed through personal perseverance to eke out a sense of dignity, independence, and meaningful contribution to her community. She has worked incredibly hard and been incredibly lucky to preserve some autonomy while still leaving something behind for me and my brother.

My personal experience with a disabled parent is just a microcosm of class in our hierarchical society. The books and magazines with inspirational stories about people with MS are almost all about the upper class who have enough money to buy their autonomy and live a meaningful life despite their disability. We, the middle class, have had to struggle and scrape to earn autonomy, but we still had a cushion and some space to do so. Who knows what happens to the underclass; I assume they’re just screwed.

Peterson’s prescription for society is horrifying to me, because I can imagine a proud, strong woman like my mother being forced to beg the rich and powerful for a chance to live. Peterson has not built a world where everyone fits; he has built one where humans are stacked into different shades of slave and master. As much as he swears that his system isn’t based in domination, it’s clear that some people are destined to be masters of the world and its meaning, while others are fated to serve these masters, whether in a literal sense or as an empty receptacle of the aspirations of greater men.

In some sense, Peterson’s political project centers around a fight against the dystopia of meaning that in some sense characterizes our society. He fails in this quest by reproducing the fundamental causes of our waste land of meaning, while promising a remedy for only the privileged few.

There are useful things to pull from Peterson. People should have access to meaningful work, relationships, and community. We need to build systems, however, that give everyone access to this, and the best way to do that is through egalitarian principles where everyone is equally valued and has a voice in the structures that rule their lives. Everyone must be given the opportunity to be both master of themselves and a slave to all. What is required is a world where all worlds fit and everyone is given the tools to build their own meaning.